There Was a Boy: My Father’s Experience During the Biafran War

I have called my father several names. When I was a child, I called him Daddy. As a teenager his name shortened to Dad, reflecting what I believed to be my growing maturity. As a young adult, I often resort back to Daddy in joyful acceptance of the truth that maturity will never rob me of my position as my parent’s child. On my phone, his name appears in Yoruba, Baba Mi. My Father. These names reflect just one aspect of my dad’s identity. For a long time, that singular identity was all that mattered to me. The idea that Dad was anything other than my dad was unimaginable as if he had only ever existed as the man that took care of me. Upon entering the gates of adulthood, I have developed a growing curiosity as to who my dad is outside of our father-daughter relationship. Who was Nathan Ugochukwu Nwabuike before he became a father? What thoughts, emotions, fears and dreams did he possess when he was a child? When I sought the answer to these questions, Dad would often respond with the details of his life during the Nigerian Civil War. As I learned more about the circumstances of the war, I gained a better understanding of how and why he navigated the world in the way that he did. The frustrating ease with which he forgives those who slight him, his stubborn persistence and lack of regard for material possessions can all be traced back to those days in Umuahia, a young boy living in the shadows of a sun that would not fully rise.

The Birth of Biafra

Before the first glimmers of Biafra fought to reach beyond the horizon of Nigeria, ethnic tension and conflict simmered beneath the surface of the nation. Under colonial rule, the region that would eventually become the Republic of Nigeria was an amalgamation of hundreds of ethnic groups. Upon gaining independence from Great Britain in 1960, the Republic of Nigeria was divided into three provinces defined by its largest ethnic groups (New Africa, 2020). The Hausa-Fulani ethnic group, a primarily Islamic people living in feudal societies ruled by theocratic elites, dominated the Northern province. The Southwest was primarily populated by the Yorubas, a mixed religious group ruled by a series of monarchs less autocratic than the Hausa-Fulani. The Southeast was dominated by the primarily Christian Igbo peoples whose egalitarian political structure reflected a largely democratic decision-making process (NewAfrica, 2020). The three ethnic groups vied for political power and dominance over various aspects of Nigerian society. In his book There Was a Country, Chinua Achebe described the unique cultural advantages that set the stage for the success of the Igbo people, even while under colonial rule. Achebe wrote,

The Igbo culture, being receptive to change, individualistic, and highly competitive, gave the Igbo man an unquestioned advantage over his compatriots in securing credentials for advancement in Nigerian colonial society. Unlike the Hausa/Fulani he was unhindered by a wary religion, and unlike the Yoruba, he was unhampered by traditional hierarchies. This kind of creature, fearing no god or man, was custom-made to grasp the opportunities, such as they were, of the white man’s dispensations” (Achebe, 2012).

Map of Nigeria from 1961 from the United States Library of Congress

True to their entrepreneurial spirit, the Igbos migrated throughout the country in pursuit of new opportunities. Igbo success sparked resentment in the North but the fuse that ignited the civil war was also political. In response to claims of election fraud and corruption, a primarily Igbo-led military coup was launched in the January of 1966. The coup resulted in the death of several key political figures including Amadu Bello, a highly respected leader from the North. Although the coup was stamped out by the Igbo General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, who would take power as President over the nation’s first military rule, the circumstances were viewed suspiciously as an Igbo plot to gain control of the country. In July 1966, a successful Northern led counter-coup resulted in the installation of Lt. Col. Yakubu Gowon as the military head of state, but the violence was not limited to the political world. In the months after the coup, roughly 8-13,000 Southeasterners were killed, attacked and robbed in the North, prompting millions of Igbos to flee back to the Southeast for safety (NewAfrica, 2020). In response to the concerns of the Igbo people Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, a military governor of the Southeast, declared the secession of the Southeastern province from Nigeria and on May 30, 1967, Col. Ojukwu declared the Republic of Biafra an independent nation (New World Encyclopedia, 2018).

The Biafran Flag

Return to the East

My dad’s family was one of the many that migrated to the East for safety. He was thirteen years old when his family returned to my grandfather’s family home in Umuahia. Dad shared of his journey from the west to the east explaining,

I was born in Lagos and grew up in Ibadan. All my siblings were born in Ibadan. I started my primary school in Ibadan and went up to primary five when the war started. Ojukwu, who at that time was in charge of the Eastern Province, had called the Igbos to come back home. So, my dad sent all of us back home to the East while he stayed in Ibadan. He was there towards the end of 1967, then he came back home. He was one of the last ones to cross the border. Once he crossed the border, that is the Onitsha border, they closed the border and no one could cross again.

Emeka Odumegwu Ojukwu pictured in June 1968.

Youth did not prevent Dad from bearing the weight of anxiety that filled the days preceding the war. “We were hearing stories; you could read it in the news and then you could see the anxiety and panic in your parents as they were trying to calm the children. Sometimes you would go to the school and parents would be so scared about what is happening…they would rush down to the school to pick up their children. It was a very rough time.”

My grandfather was hopeful that the violence and conflict would come to a quick end, allowing for a smooth return to normal but the situation in the West continued to worsen. Despite the increasing threat of violence, it was the call of a child to his father that ultimately motivated Grandpa to return to the East. Dad explained, “My dad decided to come back due to one of the letters I wrote to him. That's what he told me, but I can’t even remember that I wrote a letter. He said that in the letter I asked him what good it did for him to be making money over there and we cannot enjoy him with the money he is making. He said once he read that he changed his mind. It was good that he left then because once he came back everything shut down.”

Igbo Identity in the Civil War

Just as the pain of labour is soothed by the joy of a newborn child, Colonel Ojukwu’s announcement of an independent Biafra was met with jubilation by many of her citizens, but the Nigerian government moved swiftly to stamp out the hopes of the new nation. Only five weeks after secession, the Republic of Biafra was attacked by Nigerian forces (History.com, 2009). Dad described a firm sense of conviction among his family members and peers that Biafra would overcome the Nigerian military offensive. “Even during the war, children my own age were all excited. Everybody was learning how to do the military parade and things like that. In fact, we had so much confidence that we were going to win the war.” The people of Biafra were galvanized by their belief in the justness of their cause, seeing the war as a necessary evil to safeguard the livelihood and identity of the Igbo people. For Dad, his return to the East was an opportunity to connect with the aspects of Igbo culture and identity that he had not experienced while growing up in the West. “[In the East]…they have their own traditions like masquerades, clothing and traditional weddings. I was never involved in things like that but during the war I was able to be introduced to those things.”

Language is a particularly potent tool for the transmission and preservation of culture. American-Italian poet John Ciardi once said, “Tell me how much a nation knows about its own language, and I will tell you how much that nation knows about its own identity.” Dad told me that Yoruba was his first language but his return to the East immersed him in the Igbo language, allowing him to reclaim another aspect of his ethnic identity. Dad confessed, “I was not competent in the Igbo language at that time. Because I grew up in the West, it’s Yoruba that we spoke most of the time…Yoruba and English. We only spoke in Igbo with my dad, even my mom would always speak Yoruba. Going back to the East we made friends with others who came back from Lagos, from the North, and who came back from the middle belt. So, we started with English and within a short time we learned the Igbo language.”

Igbo identity played a significant role in the survival of the Igbo people throughout the difficulties of the war. Dad confirmed, “The Igbo believe that we are smart, we are able to create things, and we do not want somebody to dominate over us. In other words, we don’t take nonsense from anybody. So we can stand up for our rights and compete in any situation. We are gifted in creation. During the civil war [Biafrans] would look at things that were done in Japan or Taiwan and, just bring one, within a short time they will mass produce it. We are very creative.” Creativity and ingenuity were particularly necessary for the Biafran military given that the nation had no air force or navy and few military resources including weapons and trained military personnel (NewAfrica, 2020). The Nigerian army, on the other hand, was not only better equipped and trained but it also had the support of the British government (whose involvement in the war was driven by their economic interests as opposed to any moral principles).

Dad lamented over the uneven footing of the war, “Most of them [Biafran soldiers] would go out into the battlefield with limited bullets. How can you fight like that? Nigerian soldiers will just sit down with their machine guns, tie a rope on it and just pull it like that, then the thing will just be spraying. So, it was not an even battle. One was more highly equipped than the other side.” Despite their clear status as underdogs, the Biafran army withstood the Nigerian offensive far longer than anyone expected. The Nigerians reportedly believed the war would be over in 6 months (NewAfrica, 2020). With pride, Dad spoke of the Biafran-made inventions that strengthened their resistance. “Today you hear about the IED that they used in Iraq but the Biafrans were the first ones using it. It was called ogbunigwe. Sometimes it will be done in something like a bucket. They leave it somewhere and once you touch it, it will just kill people. They will do it in the form of a coffin as well. You think it is a coffin someone left there but it is a ogbunigwe.”

Ogbunigwe rocket displayed at the Umuahia War Museum. Ogbunigwe literally translates to, “instrument that kills in multitudes”. It was also called Ojukwu’s Bucket. Ogbunigwe was a weapons system composed of rocket-propelled missiles, explosive devices and command-detonated mines (Daily Focus NG, 2020).

Ojukwu also boasted of the ingenuity of the Biafran war effort. In a lecture titled Nigeria: The Truths That Are Self-Evident, Ojukwu asserted,

In the three years of war, necessity gave birth to invention. During those three years, knowledge, in one heroic bound, we leapt across the great chasm that separates knowledge from know-how. We built bombs, we built rockets, we designed and built our own delivery systems. We guided our rockets, we guided them far, we guided them accurately…We maintained all our vehicles. The state extracted and refined petrol, individuals refined petrol in their back gardens. We built and maintained our airports, maintained them under heavy bombardment.

We built armoured cars and tanks. We modified aircraft from trainer to fighters, from passenger aircraft to bombers. In three years of freedom we had broken the technological barriers. In three years we became the most civilised, the most technologically advanced black people on earth (Ojukwu, 1994).

Hardships are often heralded as the prerequisite for resilience and innovation. As Ojukwu argued, the strain and deprivation of the war forced Biafra to become self-reliant and to develop new methods of survival. But, I wonder what achievements might have been birthed had the innovation and ingenuity of the Igbo people been welcomed in Nigeria’s breakaway from colonial control. Could prosperity not have inspired the same technological advancement? The permanence of history renders these questions unanswerable, but the cost of the war makes certain that whatever was gained in those three years was incomparable to what was lost.

The Cost of the War

The initial military tact and resistance efforts that prevented Nigerian forces from advancing on Biafran territory eventually began to wane. Nigeria’s unrelenting aerial and artillery bombardment amassed severe military and civilian casualties (Hurst, 2009). The scales were tipped in favour of Nigeria when Gowon imposed an economic blockade on Biafra, preventing the import of food, medicine and weapons by land, air and sea (New World Encyclopedia, 2018). The blockade led to widespread civilian hunger and starvation which had devastating impacts on Biafra’s youngest citizens. Images of “the starving African child” that have shaped Western conceptions of Africa were first disseminated on a global stage in response to the Biafran humanitarian crisis (NewAfrica, 2020). It is estimated that 3,000-5,000 Biafrans died daily due to starvation (Hurts, 2009).

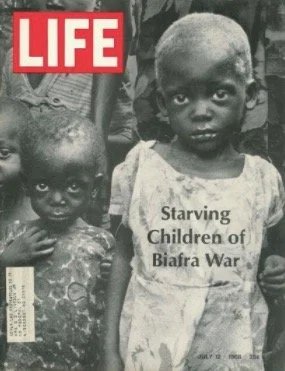

July 12, 2968 Life Magazine cover.

Children with Kwashiorkor, a disease caused by severe protein malnutrition that results in bilateral extremity swelling, were shown to Western media to draw attention to the atrocities of the war.

By nothing less than a miracle, Dad’s family was largely spared from the severity of deprivation during the war. Dad explained,

Those who were not fussy about food were able to excel, you wouldn’t even know that things were very hard for them. Since everybody knew that we came from Ibadan, we came from a university campus, they looked at us with a different focus and Dad was very respected so that respect given to Dad was extended to his own children. Because of malnutrition, there was what is called kwashiorkor that affected so many children. One of my siblings, he is the type that is very picky about his food, so that affected him but to God be the glory, when that happened it wasn’t long until the war ended and within a short time, maybe about 6 months, after the war ended, we went back to Ibadan and then he recuperated.

Death is not the only cost of war. War strips away the innocence of those who manage to survive. As an adolescent boy, Dad should have been learning in a classroom and playing football with his friends. Instead, he was preparing for the threat of violence. Dad shared the details of his daily life during the war,

I began to learn how to weave baskets and learned how to do the Nigerian mats. I helped with household chores and went to the farm with my parents. The belief was that the Nigerian soldiers would come with parachutes. We put something like pegs all over the field [of the school] so that if they land it will create some harm for them. We had to dig a trench on our own and cut the big palm trees to put on top with sand. When there was a siren that went on to signal that a plane is coming to bomb, we will run into that place. So, there’s always an exercise that goes on every time for your safety.

Some children were more heavily involved in the war efforts, going so far as to cross enemy lines as spies. Dad reminisced of his friends that had supplied Biafran soldiers with information. “They would recruit and train them, and they would send them to the battlefield as people who have lost their parents, orphans, and then the Nigerian soldiers would pick them up and cater for them, not knowing that those kids are spying. After some time, they would disappear and come to report to the Biafran soldiers. As a result of that, when the Nigerian soldiers realized what was happening, some of them were killed.”

Not only did the war affect Dad’s daily routines and habits, but it also influenced his psychology. His survival instinct claimed the energy and attention that would otherwise be reserved for the largely inconsequential thoughts and worries of the average teenage boy.

We could tell when there is a shell coming. We learned to program ourselves because when you hear the shell is shot, you could count, 1,2,3,4,5…then you know where it is going to land. So, your mind begins to create ways of survival. I knew every kind of bomb that is sent. When they were shooting a gun I would say, ‘Oh, that is a Mark IV they are shooting…that is this kind of gun.’ That is again a survival instinct.

Before the war, if I had heard someone had died on this street and they send me to go and buy bread there I would never go because I was so scared. But during the war, that is something that you see all the time so maybe your body just becomes immune to it.

Describing the innocence of childhood, the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote a piece entitled, “Childhood is the Kingdom Where Nobody Dies.” War destroys that kingdom, forcing the young to become well acquainted with death. Dad explained,

Death becomes nothing to you. When we were moving from, for example, Mississauga going down to Brampton area, along the street you’ll just see dead bodies who have been shot and killed. And sometimes you will run into the bush and you’ll be there two or three days. No shelter nothing because you are hiding, and the rain is coming there. What can you do? Your parents can spread their clothes like a tent and that’s all you can do.

We didn’t stay in the tent for so long. From there were went in to Umudike where there was a school. That’s where we camped and we were there for a couple of weeks then the war ended and we were able to go back to our house.

Nigerian forces launched their final offensive, Operation Tail-Wind, on January 7, 1970, under the leadership of Col. Olusegun Obasanjo (New World Encyclopedia, 2018). Biafran forces surrendered less than a week later and Ojukwu subsequently went into exile in Côte d'Ivoire. The Igbo people were left to pick up the pieces of their lives, returning to a nation that had nearly destroyed them. Dad’s family readjusted quickly, returning to jobs and schools in Ibadan. There was no time to ruminate on what had been lost during the war as the task of rebuilding required their full effort.

Over 50 years later, the same tension and hostility that preceded the war continue to simmer. Concerns of marginalization and oppression still weigh heavily on the Igbo people. But Dad’s optimism is unflinching in the face of these realities.

I still have hope because [Igbo people] are very resilient. They will always survive no matter what, because if they can survive what happened in that three year war, they will survive. There is hope, yes there is hope. They are like the children of Israel, even if it is just two that is left they will reconvene back again and survive.

Dad relayed his story with a surprising matter-of-factness. The hardships of the war are not something he thinks about often, but when he does it is with an acceptance that the past cannot be changed and with gratitude for God’s continued protection and favour. In his letter to the Philippians, the Apostle Paul wrote, “I know how to be brought low, and I know how to abound. In any and every circumstance, I have learned the secret of facing plenty and hunger, abundance and need. I can do all things through him who strengthens me” (4:13). Dad’s life exemplifies this unwavering contentedness. I believe those years in the war taught him the secret of enduring lack and need while cultivating the ability to cherish seasons of abundance. While I do not envy his war stories, I covet his endurance. By sitting under his story and that of other survivors, I hope to claim my inheritance of the resilience and fortitude of Biafra.

References

New Africa. (2020, April 22). An Honest Explanation of the Nigerian Civil War | The Biafran Story. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7JCvIvb8PpY&t=1702s

9 Wonderful Inventions By Biafra During The Civil War. (2020, March 7). [Photo]. Daily Focus Nigeria. https://dailyfocusng.com/9-wonderful-inventions-by-biafra-during-the-civil-war-photos/

History.com Editors. (2019, July 27). Civil war breaks out in Nigeria. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/civil-war-in-nigeria

Hurst, R. (2019, May 9). Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970). Black Past. Retrieved December 24, 2021, from https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/nigerian-civil-war-1967-1970/

Nwaubani, B. A. T. (2020, January 15). Remembering Nigeria’s Biafra war that many prefer to forget. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-51094093

Ojukwu, E.O. (1994, February 22). NIGERIA: The Truths Which Are Self-Evident. The Sunday Magazine Anniversary Lecture, Nnewi, Anambra, Nigeria. https://nigeriaworld.com/feature/speech/ojukwu_archives.html